Next weekend – that is, on Palm Sunday, 25 March 2018 – I’ll be performing at St Stephen’s Richmond on the invitation of the parish organist, who heard my two churchy albums, liked them, and thought perhaps I could do a third instalment revolving around music for Passiontide and Easter. It’s always so lovely when one’s music reaches receptive ears, but for it to generate an invitation to further creation is really exciting. I accepted immediately and I’m really looking forward to playing.

Next weekend – that is, on Palm Sunday, 25 March 2018 – I’ll be performing at St Stephen’s Richmond on the invitation of the parish organist, who heard my two churchy albums, liked them, and thought perhaps I could do a third instalment revolving around music for Passiontide and Easter. It’s always so lovely when one’s music reaches receptive ears, but for it to generate an invitation to further creation is really exciting. I accepted immediately and I’m really looking forward to playing.

Except.

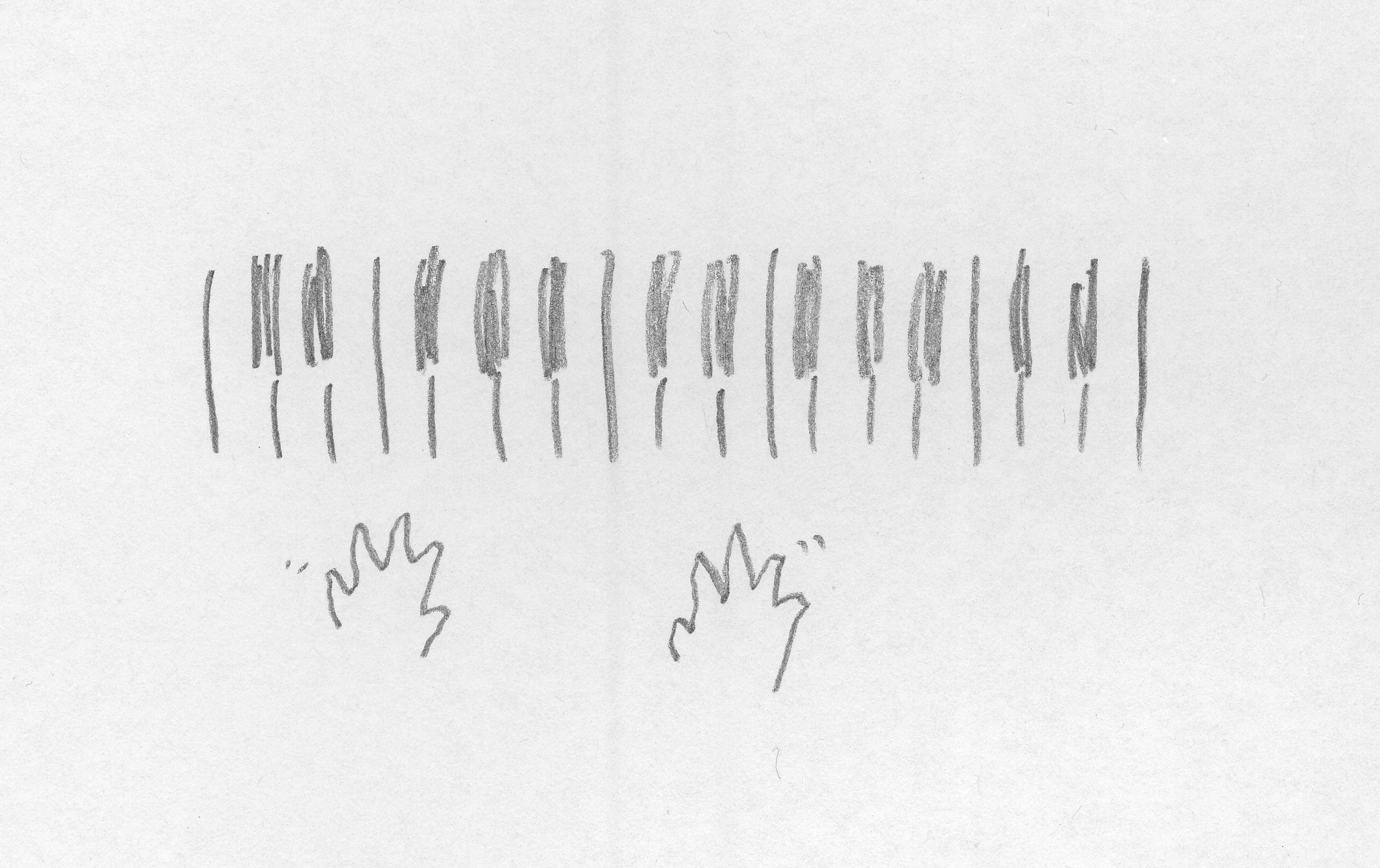

What do you do ahead of a recital of improvised music? Like I’ll tell you later and I’ll tell you later in December, this performance will take models from the literature, hymns generally but other pieces also, and the improvisation will endeavour to relate to – to draw from, to (dare I say?) contextualise, to introduce – them. They’re generally not overly-complicated selections and I’ve known them for most of my life. So what do I practise?

Well, I suppose I try to practise contextualising them, introducing them, placing them in sympathetic improvised surroundings. When I made Life’s undertow there was no preparation that I recall. It was completely improvised and I wanted it to be fresh so I tried not to anticipate anything. In preparing for the first church program in 2014 though I did practise the whole thing, the whole hour’s worth, a number of times, and even recorded several of the attempts, just to make sure I had the dimensions right and I wasn’t going to be trawling over the same stuff six times in the same program.

But there are two really dumb things you can do ahead of an improvised performance. Firstly, you can watch the DVD of Keith Jarrett’s Tokyo Concert (2002). This is a big mistake because his work is so original and so stunningly well-delivered and so comprehensive in its aesthetic coverage that you won’t feel like playing anything at all for a little while after viewing. So advisedly, you don’t do that. Secondly, you can play one of the pieces you’re intending to play publicly, in private, really well, so that you’re satisfied that you knew what you were doing and you did it right and the whole thing came across as an acceptable whole, making its point, apologising for nothing. Because then, can you do it again? Or will you be trying simply to recapture what you just made? And is this even possible? And if you try, will you either miss (most likely, because it’s gone now), or perhaps simply feel dishonest for attempting to recapitulate what was achieved honestly in that (rather than this) moment?

I had a friend at school who used to call me Felix and all I can remember of why is that there was some character in something to which he’d been introduced who carried on about constant change and how he couldn’t do what he did a minute ago because he was different now – I guess my friend was saying something about my overwhelmingly exposed artsiness or something or other. (He couldn’t sing ‘Happy birthday’ so you’d recognise it, so music was not his thing. [And that’s quite okay.]) Funnily enough, although as an impressionable teenager I might have been upset that he wanted to pick on me for whatever, now I find he was probably onto something. Because it’s true. That there is gone now, you can’t revisit it. Even if you recorded it, you can only revisit it by listening, not by playing. Or if you do, it won’t be improvised anymore.

So I’m preparing by thinking, as well as playing. Thinking more than playing, probably. Or playing other stuff, so that I’m at the keyboard but not getting ahead of myself and delivering the concert to the furniture in my practice room. I know (if experience is any guide) that I’ll be surprised by whatever I dig up on Sunday afternoon, and I’m putting some faith in my customary capacity to discover not deserting me when most it’s needed.

If you’re reading this and you’re anywhere near local, why don’t you think about coming along. I’d love to see you there. 4pm. Mwah.

20/iii/2018