When one name is enough. Like Keith. Miles. Billie. Duke. When the contribution is so sizeable and so distinctive that there can be no confusion. You might say, well Wynton is an unusual name, and around here it is. But there was Wynton Kelly, wasn’t there? And he was terrific; his comping on Miles’s Live at the Blackhawk records is still a template for piano players working on small-group jazz performance. But we say Wynton, and we know who it is that we mean.

When one name is enough. Like Keith. Miles. Billie. Duke. When the contribution is so sizeable and so distinctive that there can be no confusion. You might say, well Wynton is an unusual name, and around here it is. But there was Wynton Kelly, wasn’t there? And he was terrific; his comping on Miles’s Live at the Blackhawk records is still a template for piano players working on small-group jazz performance. But we say Wynton, and we know who it is that we mean.

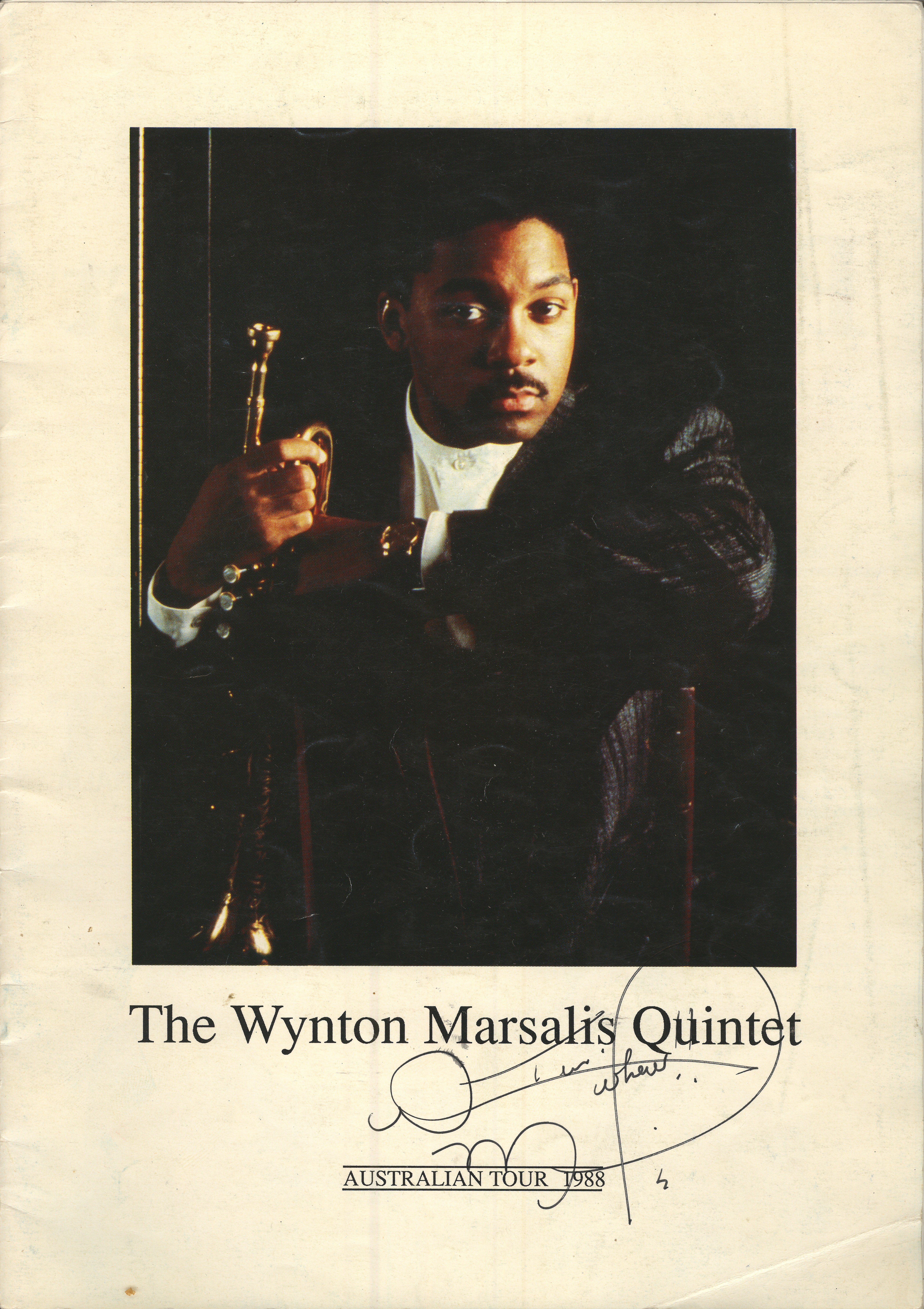

So I shall refer to him here, trusting that he mightn’t mind. I first heard Wynton in concert in 1988, when I was sixteen, and the performance took place in what was then called the Melbourne Concert Hall. His band included Marcus Roberts on piano, Reginald Veal on bass, and Herlin Riley on drums, as well as Todd Williams on tenor saxophone. It’s a very, very long time ago (although I do recall they performed ‘The very thought of you’). In the printed program, of which I bought a copy, there was an interview between Wynton and Stanley Crouch, that had previously been published in Down Beat. I was very new to jazz, so I read it closely.

Wynton is very high-minded when he speaks of the challenges of studying and performing jazz music. Stanley Crouch asks, ‘How do you respond to the assertion that you and your musicians are no more than neo-conservatives muddling through a swamp of sentimental nostalgia instead of innovating?’ and he replies:

It’s my position that very little thorough information regarding the music of John Coltrane, the jazz Miles Davis, Charles Mingus, Monk, or Ornette Coleman is possessed by those who use terms like “nostalgia” and “neo-conservative”. Nowhere do I hear these group conceptions being tackled, and nowhere do I hear that level of improvisational authority exhibited within those forms. Are we, therefore, to conclude that the works of these musicians are not strong enough foundations upon which to develop? Or could it be perhaps that this music is just too difficult for those who know that it demands staying up all night transcribing the components of albums like Filles de Kilimanjaro, Crescent, Mingus Presents Mingus, and The Shape of Jazz to Come?

This was ridiculously exciting to read. As musical challenges go, this seemed top-drawer stuff. Before too long I was lining up at Gaslight Records (remember?) for all four of these albums. The Mingus on CD (a little later), but the others on vinyl. Filles de Kilimanjaro is still in my top five records of all time, and Crescent is easily my favourite Coltrane. (I did some transcribing too, by and by.)

I had come along to hear Wynton because he was huge and more or less the face of jazz at this time, at least where I was sitting, and my brother had a copy on LP of Black codes (from the underground) that we had played and played and played. I didn’t know at this stage what was written and what was improvised – I had no idea about jazz performance practice or anything but I found the music so appealing, so interesting, so infectious, and I wanted more. So J Mood followed Black codes, and this was the album on which the quintet was touring in 1988. It was also one of the first two CDs that I bought. (The other one was Browne, Costello and Grabowsky, Six by three.)

This was the time that Sting had taken off with what had been Wynton’s band! – or so they said. In fact, he’d persuaded Kenny Kirkland and Branford Marsalis to join him for the recording of The dream of the blue turtles and subsequent tours. I don’t remember in detail what went on but as I recall – or perhaps, as I have heard here and there since – it was a bit of a crisis, rather I suppose like when the Red Onions split and The Loved Ones were born.

The musicians who stayed as Red Onions consolidated their devotion to jazz with two studio recordings, King Oliver Revisited (EP, 1965) and Big Band Memories (LP, 1966). These recordings ‘demonstrate a renewed conviction, manifest in challenging repertoire and the hard work by which it has been adopted.’ (Timothy Stevens, The origins, development and significance of the Red Onion Jazz Band, 1960-1996, PhD Thesis, University of Melbourne, 2000: 160). In his liner notes to J Mood, Stanley Crouch writes that the ‘startling finesse’ of the album marks ‘yet another step up to higher ground’ for Wynton Marsalis. In today’s world, Crouch writes, ‘pop forms, ineptitude, and trivial trends are discussed with a sociological seriousness that avoids the issue of artistry and of professional levels of technical control. Sellouts are applauded and frauds are showered with explanatory ink. Fumbling or pretentious eccentricities are misconstrued as innovative.’ Wynton, on the other hand, is said to be developing a rhythmic complexity and spontaneity that draws from earlier masters and demonstrates enormous originality, his tone is ’rounder and more clarion than ever’, and the recording is ‘a declaration of war against the contrived and the worthless. […] J Mood shows how safe the warm soul of jazz is in the winter of our world.’ (Stanley Crouch, notes to Wynton Marsalis, J Mood (CBS 1986))

Cleaving to things that matter is, it seems to me, something entirely defensible. There are things that you feel have made you who you are, and you don’t wish to surrender them. You have seen possibilities for work and exploration and you’d like to be permitted to work and to explore. Any thing that exists as thing has characteristics peculiar to it, it identifies as that thing by some means or another; you recognise it and you have developed affection for, connection with, it. It could be anything. A hobby, a livelihood, a passion. Whatever. Your seriousness in pursuit of that thing is part of your character, and perhaps (as that book title goes) ‘as serious as your life’ (Val Wilmer, As serious as your life: Black music and the free jazz revolution, 1957-1977, Allison and Busby, 1977).

Now I never watched the Ken Burns series on jazz that a lot of people seemed to hate. In what I heard it was cast as Wynton’s own creation, things told entirely from his point of view, too many meaningful and important things left out because they didn’t fit his narrative. Again: I didn’t see it, so I don’t know. I do know that Wynton has had a reputation for being on the inflexible side about what jazz is and how it should be used. In his Sweet swing blues on the road (New York: Norton, 1994) he speaks with students and when they ask about European jazz (for example) he stipulates that in order to be jazz, the music must contain blues and swing.

In jazz it is always necessary to be able to swing consistently and at different tempos. You cannot develop jazz by not playing it, not swinging or playing the blues. Today’s jazz criticism celebrates as innovation forms of music that don’t address the fundamentals of the music. But no one will create a new style of jazz by evading its inherent difficulties. (Ibid., 141).

He is however inclusive, even according to these directions:

‘Why are the best jazz musicians black?’

‘As Crouch says, “They invented it.” People who invent something are always the best at doing it, at least until other folks figure out what it is. America made the best cars for decades, until it forgot the essence of the manufacturing system it had created. Swinging the blues is about culture, not race. If you celebrate less accomplished musicians because you share a superficial bond, you cheat yourself. Anyway, if you ask most black Americans today who is their favorite jazz musician, they will name some instrumental pop musician. So much for race. The younger musicians of any racial group today swing in spite of their race, not because of it.’

‘Are you saying white musicians can’t play jazz?’

‘Jazz includes everyone. That is further proof of its greatness. It accepts and nourishes all who want to participate.’

‘Why are you so serious?’

‘Because, as Mr Murray says, culture is life-style, and wars are fought over what style of life a society will lead.’ (Ibid., 142-5)

Growing up in Melbourne, coming to jazz after spending several years learning classical piano and flirting with pop music as a teenager, blues and swing were as foreign to me as putting the metronome on 2 and 4. But I tried to acquaint myself with all these things, just as I learnt standard tunes, and although I have emerged as someone who writes and performs original music that is not entirely blues and swing based, those things are now in there somewhere as well. And what Wynton demonstrated to me all along was integrity. His clear and incontestable devotion to the music he admired and to which he wanted to contribute was always affecting, and the seriousness with which he approached instrumental craft, compositional endeavour, and ensemble expression was stunning.

I have heard him several times when he has visited Melbourne, in smaller and larger groups, and once saw him with members of his band after hours at Bennetts Lane. This was genuinely unforgettable; there were sit-ins and even a cutting contest. It’s not what I do myself but to see it done by people for whom it is part of the language was breathtaking. ‘Spring Yaoundé’, in I think the State Theatre (although I could be misremembering this, I’m not entirely certain) is another moment I’ll not forget. His body of work is immense, and still growing, and the range of things to which he has devoted his energy is staggering.

So last night, March 2, 2019, I was at Hamer Hall to hear the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra. I hadn’t been going to go to this concert because it was pricey and I felt I had seen Wynton a good few times before. But then he was interviewed on The Music Show by Andrew Ford and suddenly I was reminded, in the way that sweeps over and fills the body, of all the jazz things that I’d loved and pursued all those years ago, the example of Wynton sending me deep into Bud Powell and Thelonious Monk, singing Charlie Parker solos in the car as I drove with them on tape, considering Lester Young’s rhythmic placement in ‘I must have that man’. The joy of it all. It came flooding back. Wynton said, ‘Excellence is a form of protest.’ I was gone. I bought a ticket.

The concert, with three pieces by Duke Ellington, the Prelude, Fugue and Riffs of Leonard Bernstein, and after the break Wynton’s Symphony no. 4: The Jungle, was astonishing. The use of the orchestras in tandem was miraculous and the grooves that were generated from these massed forces were spellbinding. Instrumental improvisation was to the point, individual features seemed in perfect dimension to the larger work, and nothing was ever overdone. The symphony’s conclusion was surprising beyond belief and the audience – which had been clapping individual movements with enthusiasm as the piece went along – was silent for ten seconds when things finally faded out. Wynton’s trumpet is always a sensation but he was not forever making himself the feature and the work was genuinely collaborative.

Afterwards, I walked around to the stage door. I had brought both my copy of Sweet swing blues and the program from the 1988 concert. And a pen. I met a student there, and we chatted, and one of the violinists from the orchestra whom I know appeared too so it was lovely to speak with her. It was over an hour before Wynton emerged but when he did there were perhaps twenty people waiting to see him. He was patient and gracious, and shook people’s hands and heard their stories and signed programs or tickets or CDs, hurrying nothing although drinks were waiting around the corner. My turn came, and I said, I can’t tell you how you’ve influenced me or how grateful I am for the work you’ve done. And he shook my hand and looked genuinely humble as he thanked me, before signing my book and my program (see accompanying picture: it says, ‘Tim. Whew!!’) and having several photos taken.

It was a meeting with a hero, dramatic as that may sound. Wynton has taught me volumes about doing what you feel needs to be done, respecting forebears but striking up for new lands. My music does not now, nor will it ever, resemble his, but I have made it in a spirit of honesty that I hope is conveyed to the listener, and one of my greatest examples of this comes from Wynton. I walked through the city to meet Sall, who was picking Freddy and a friend of his up from a party in Lonsdale Street. I was so very happy to have gone along to the concert, and to have waited out the back to offer my thanks to this man whose music has meant so very much to me. And now I am getting back to work.

3/iii/2019